Symbiosis, the “slurry” method and why metagenomics is basically the same thing as astrophysics

Published:

A big challenge and thrill in studying microbial symbioses is the fact that sometimes unrelated organisms can form tight communities virtually impenetrable to us, the outsiders. If you want to study a complex system, it helps to take it apart and examine the components individually - but sometimes the symbionts rely so much on each other we can’t isolate them.

Lichens, the fungal-algal symbioses, exemplify this problem. In 2016, Spribille et al. showed that many lichens contain a previously unknown component - unicellular fungi, or yeasts. During the next five years other studies confirmed that the yeasts are widespread and ubiquitous in lichens, but couldn’t tell much more about them. The yeasts have not been isolated in pure culture yet - and not for the lack of trying.

Our recent paper in Genome Biology and Evolution presents the first evidence on the role yeasts play in lichens. My coauthors and I got this evidence using metagenomics - a set of techniques that deals with sequencing data from intact microbial communities.

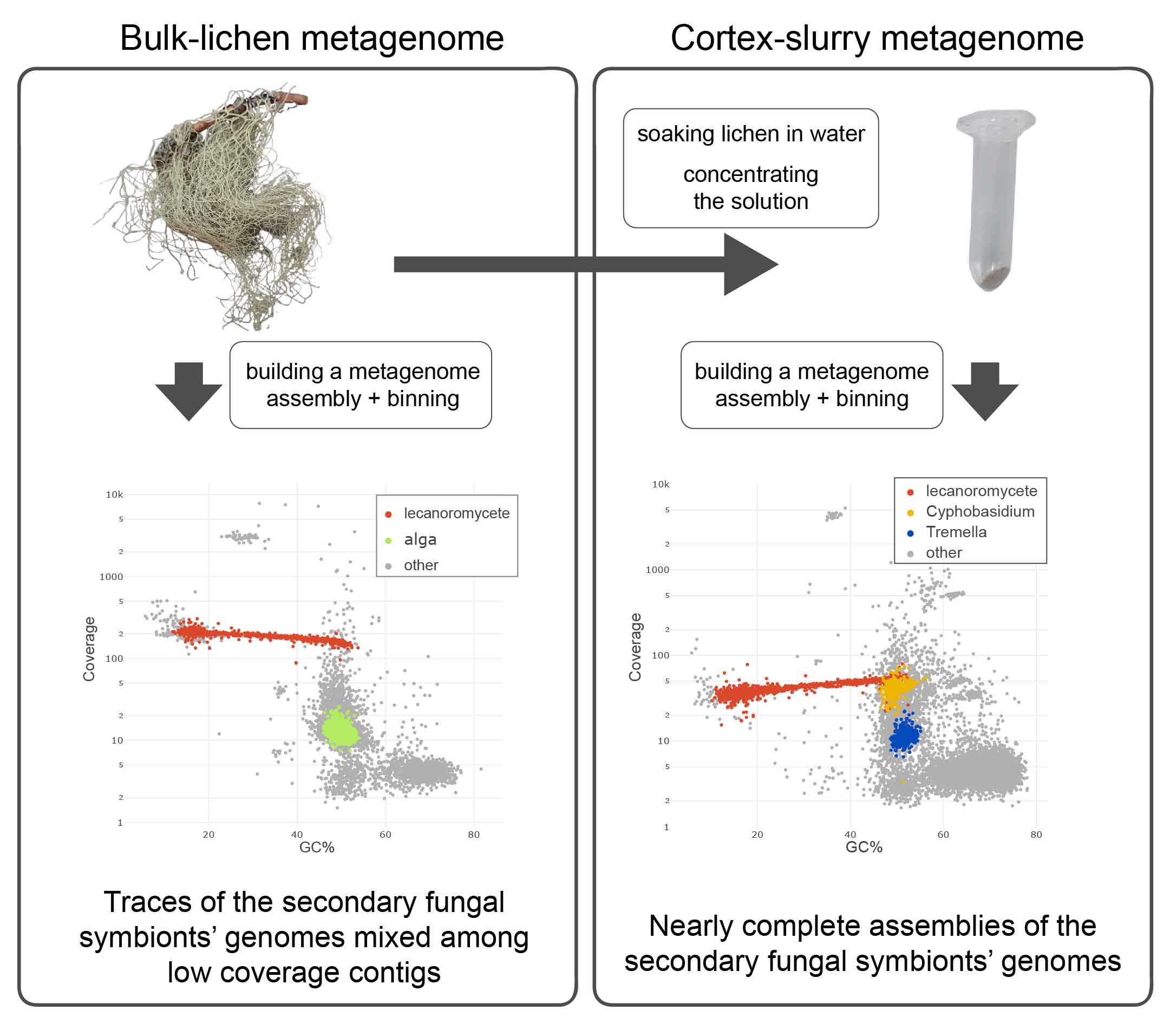

To immediately complicate things, I have to put an asterix on “intact”. One innovation that proved crucial for our study did require some lab work. The “cortex slurry method” is a lifehack that helped us to solve two problems with lichen yeasts: their numbers are low (less than one yeast cell for 100 cells of the “dominant” fungus), and they are embedded in a polysaccharide “cement” that covers the lichen from the outside. To make a sample enriched in yeast cells, I used a set-up similar to a washing machine: I put a lichen in warm water and shaked it for a few hours. Water dissolved the polysaccharides - and the yeasts ended up in the solution, which I spinned down and used the resulting slurry for the next step. Fun fact: Anglesea et al. (1986) actually used commercial washing powder for the same purpose.

Back to metagenomics.

“Microbial dark matter” is a term that is often used to describe the microbes that biologists are unable to culture. I want to take this metaphor one step further and say that studying uncultured microbes via metagenomics is somewhat similar to astrophysics. We can’t touch the stars or run experiments on them, but this doesn’t mean we can’t study them. Same goes for microbes.

Sequencing machines are the radiotelescopes of microbiology. They create massive amounts of extremely noisy data that can tell you a lot but only after you decipher it. Thanks to my coauthors from the EMBL-EBI, we were able to extract nearly complete genomes of two species of lichen yeasts from the cortex slurry metagenome. I compared these genomes to genomes of other fungi including the “dominant” fungal partner.

Three things that I learned from the genomes: 1. The yeasts might be involved in nutrient scavenging and in production of the polysaccharide “cement” that embeds them, 2. The yeasts probably do not contribute much to the secondary metabolite production, and 3. Contrary to some hypotheses, the yeasts do not look like parasites - or at least not more than the “dominant fungus” does.

These results are yet to be confirmed experimentally - and in fact I will get back to it as soon as I finish writing this blogpost - but what this study demonstrates clearly is that bioinformatics and hot water can help to crack even the more recalcitrant symbiosis.